New spaces and expanding influence

1965 – 1974

by Andrew Myers

Some people call research a rat race, but I don’t know of anything else in the world I would rather be doing.

— Clayton W. Bates Jr., 1983

1965 – 1974

In May 1965, just days after Fred Terman had announced his retirement as vice president and provost of Stanford, a renovated 16,000-square-foot building across from Engineering Corner—one of the early engineering buildings where Terman’s office had been during the time he was teaching and chairing the Department of Electrical Engineering before World War II—was named in his honor. Stanford President Wallace Sterling and two of Terman’s former students—Engineering Dean Joseph Pettit and David Packard, now a Stanford trustee and Hewlett-Packard board chairman—were among the speakers.(1) “If I could relive my life I could not do any better than to play the same record over again,” Terman told the Stanford Daily.(2)

New spaces and frontiers were abounding. In October 1965, after four years of construction, the Department of Materials Science—which in 1971 would become the Department of Materials Science and Engineering—celebrated the dedication of its new home, the Jack A. McCullough Building, made possible by a $1.5 million grant from vacuum tube pioneer Jack McCullough and his wife and from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The building still serves as a center of interdisciplinary materials research today.(3)

The Department of Chemical Engineering, just five years old, had grown weary of its under-resourced home—“a dilapidated one-story sandstone storage building known quaintly as the ‘outhouse.’ ” In 1965, the department moved into a new “laboratory and gazebo” building through a grant from the National Science Foundation, with matching gifts from Mr. John Stauffer and other private donors.(4)

In 1967, the school broke ground on the Space Engineering Building: a $4,460,000, four-story, 116,000-square-foot home for the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, with faculty offices, labs, shops, a large computer facility, and a 210-seat auditorium serving 50 faculty members, 40 research associates, and 180 graduate students from a dozen departments in the schools of Engineering and Humanities and Sciences. Funding from NASA and the U.S. Air Force, along with several private and corporate gifts, made possible a new era in space-oriented research and education.(5) When the building opened in 1969, it was named for the late Stanford professor William F. Durand, who, Dean Pettit noted, had been one of the first at Stanford to receive a government award of $5,000 for propeller research during World War I. “It resulted in his development of the first variable pitch propeller, and marked the beginning of aircraft studies at Stanford,” Pettit said.(6)

The William F. Durand Building for Space Engineering and Science, 1969. The building was built to house the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. During this time, the department was receiving more than $1 million in research funding each year and more than 200 graduate students enrolled, surpassing MIT as the nation’s largest producer of PhD graduates in aeronautics and astronautics. | Stanford News Service.

With more than $1 million in research grants flowing in yearly, and more than two hundred newly minted graduate students flowing out, Stanford became the nation’s leading source of PhDs in aeronautics and astronautics.(7) That upsurge owed much to the efforts and academic contributions of department chair Nicholas Hoff.

First faculty in space

During the heated space race of the 1960s, NASA selected Stanford electrical engineer Owen Garriott for its inaugural class of six scientist-astronauts.(8) Garriott would venture into space in 1973 with the Skylab 3 mission, during which he worked the first amateur (ham) radio station in space, connecting with some 250 ham operators, including his mother, Mary Catherine Garriott, Senator Barry Goldwater, and King Hussein of Jordan.

In 1973, Krishnamurty Karamcheti, a professor of aeronautics and astronautics, entered an agreement with the NASA Ames Research Center to establish the NASA–Stanford Joint Institute for Aeronautics and Acoustics (JIAA) to study the emerging field of flow-generated noise that had grown in importance in the age of commercial jets. Over the next quarter century, JIAA would graduate forty-five PhD students.(10)

Electrical engineer Owen Garriott on board NASA’s Skylab 3, where he worked the first amateur radio from orbit, 1973. He also performed three spacewalks, logging 14 hours outside of Skylab. In the inaugural class of six scientist-astronauts selected by NASA in 1965, Garriott went on to fly on board a Space Shuttle mission in 1983, logging a lifetime total of 69 days, 18 hours, and 56 minutes off the planet. | NASA.

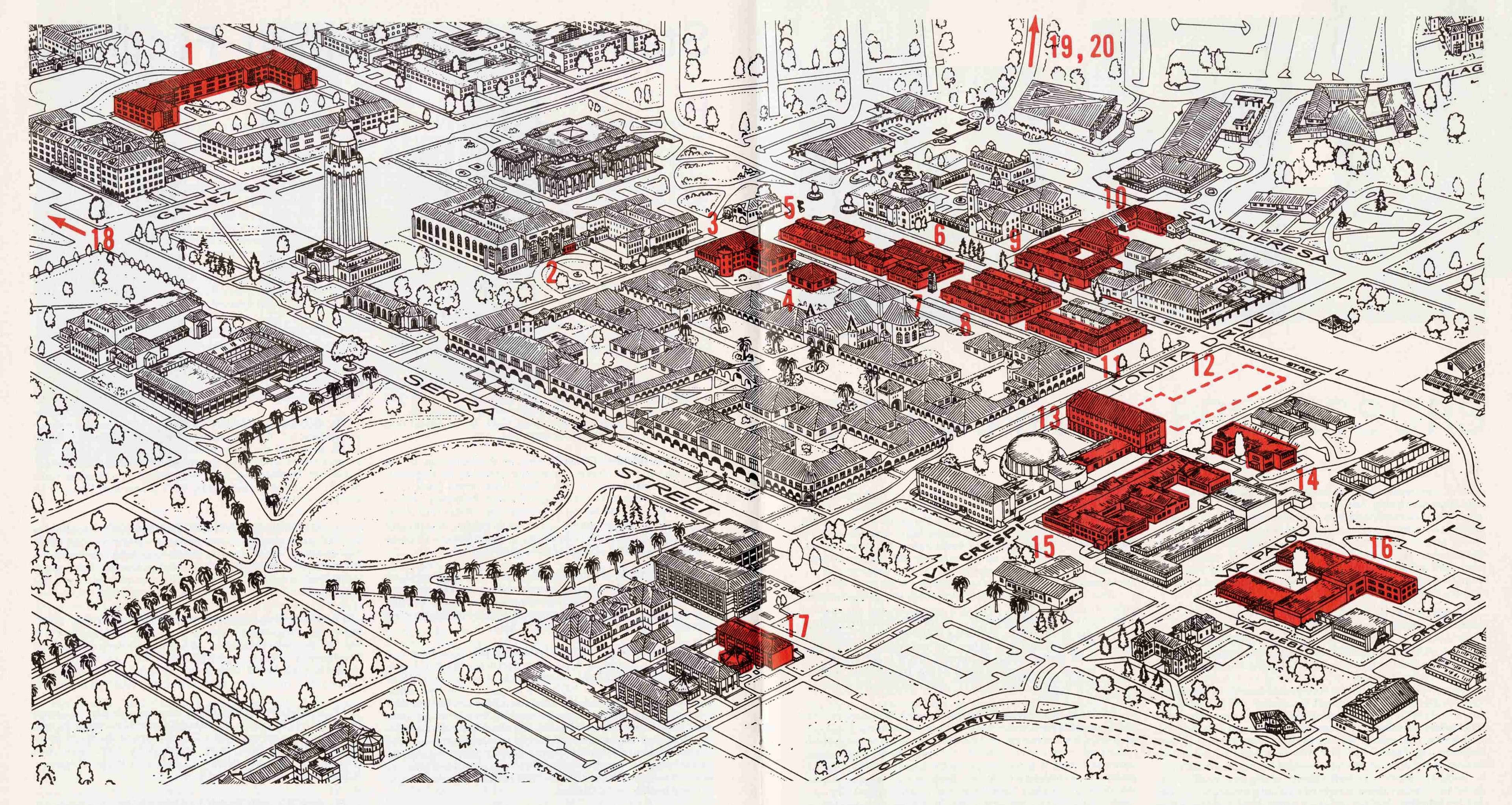

Stanford Engineering

Facilities Map, November 1966

Campus facilities had been expanded, remodeled, and reconstructed almost continuously since the university opened its doors for students in 1891. At the time this map was published, some radio science research was conducted elsewhere in California and as far away as Antarctica. One major new building, the Space Engineering Building (later named for William F. Durand), was under construction.(9) A summary of the extensive facilities follows (numbers correspond to the buildings shown on the schematic drawing). | Special Collections & University Archives.

The computer age

In January 1965, when the School of Humanities and Sciences created the Department of Computer Science, Stanford became one of a handful of universities with such a full-fledged department. Campuswide, computers were transforming a broad range of fields, including engineering, genetics, music, and robotics. The Department of Computer Science would find a permanent home in the School of Engineering two decades later.

The DENDRAL program—short for “Dendritic Algorithm”—was the world’s first “expert system,” uniting the skills of early artificial intelligence champion Edward Feigenbaum and Nobel Prize–winning geneticist Joshua Lederberg. The system was able to computationally estimate the molecular structure of various compounds from mass-spectrogram data. DENDRAL would eventually prove more accurate than human chemists in its ability to automate decision-making and problem-solving in organic chemistry.

At the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (SAIL), professor John McCarthy, lecturer Lester Earnest, and doctoral candidate Rodney Schmidt applied new AI abilities to a robotic vehicle known as the Stanford Cart, which by the late 1970s would be able to navigate visually through the foothills above campus. The Stanford Cart was first imagined as a robotic lunar rover when it was introduced in 1961 by mechanical engineering graduate student James L. Adams, who later joined the faculty. It became one of the world’s first self-driving vehicles.(11)

SAIL colleague John Chowning, a PhD student in music, formed a computational music group that would evolve into the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA).(12) In 1967, Chowning presented his frequency modulation (FM) synthesis algorithm to the world. It was a “simple yet elegant” breakthrough in the synthetic production of musical timbres. In 1973, Chowning licensed the technology to Yamaha, where it became “the most successful synthesis engine in the history of electronic musical instruments.”(13)

Visitors from France at the Artificial Intelligence Lab on computer music, 1975. Seated from left: Pierre Boulez, Steve Martin; standing from left: Andy Moorer, John Chowning, and Max Mathews. A computational music group founded by Chowning evolved into the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), which launched in June 1975. Because of the growing reputation of the computer music group at Stanford, Boulez had asked the team to participate in the planning stages of a music research institute being formed at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. | Stanford News Service.

In 1968, the Computer Forum, an industrial affiliates initiative, formed under the oversight of professors Edward McCluskey, Arthur Samuel, and William Miller. The Forum endures today, bringing more than one hundred corporate members together with academic and industrial leaders in computer science and electrical engineering to shape the future.(14)

In the 1920s, the challenge of the day had been long-distance transmission of electricity. Fifty years later, it was long-distance transmission of data—and Stanford engineers were once again ready. In the 1960s, the U.S. Department of Defense established the ARPANET project to create the first wide-area “packet-switching” network. Packet-switching, which divided and sent data in small packets and reassembled them at the destination, was the technical foundation for what would become the Internet. On October 29, 1969, the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) received the first message—“LO”—ever sent over the ARPANET from its first node at UCLA, making Stanford the second node.(15) In 1971, SAIL successfully joined the growing ARPANET, too, helping pave the way for further breakthroughs from Stanford.

In 1974, electrical engineering and computer science Professor Vinton Cerf, Robert Kahn of DARPA, and some of Cerf’s students published the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), which governed how packets of information would be transmitted over the ARPANET and, eventually, the Internet. For this work, Cerf and Kahn would later be named corecipients of the Association for Computing Machinery’s 2004 A.M. Turing Award.

Meanwhile, Ed Feigenbaum and Joshua Lederberg continued their interdisciplinary partnership, demonstrating ARPANET’s abilities as a tool for collaborative research with SUMEX-AIM (Stanford University Medical EXperimental Computer for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine), a national network of computing resources for artificial intelligence in the biomedical fields, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health.(16)

SAIL was also busy making strides in robotics. In 1969, mechanical engineering student Victor Scheinman developed a prototype six-jointed robotic arm that was a forerunner of the assembly-line robotic arm.(17) Two such arms were mounted on a tabletop at SAIL and used in research and teaching for more than two decades.

Even with those successes, computers were not above criticism. As the Vietnam War dragged on, in February 1971 a group of seventy students led a twelve-hour seizure of the Computation Center to protest the U.S. bombing of Laos. They chose the Computation Center as “the most obvious machinery of the war.” The protest resulted in numerous arrests.(18)

In 1974, the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) named Stanford’s Donald Knuth as the ninth winner of its A.M. Turing Award.(19) Knuth’s 1968 textbook, The Art of Computer Programming, would be printed in more than a million copies and be cited in the American Scientist’s list of books that shaped the last century of science.(20)

Growing disciplines, expanding influence

With the help of economics professor Kenneth Arrow, the discipline of Operations Research became a full engineering department in 1967.(21) George Dantzig had joined the faculty just one year before; he would later be known as the “Father of Linear Programming” for developing the simplex method of mathematical process optimization. The simplex algorithm would be named as one of the top ten algorithms of the twentieth century and would transform “virtually every industry, from petroleum refining to the scheduling of airline flights.”(22)

A training grant from the U.S. Public Health Service and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission produced, in 1965, Stanford’s first-ever course in nuclear civil engineering under Professor Paul Kruger. In the class, graduate students and faculty explored the feasibility of using tactical nuclear explosions in construction and industry. The class was keenly focused on water quality and pollution control. Guest lecturers included Manhattan Project physicist Edward Teller and Nobel laureate Willard Libby.(23)

Also in 1965, associate professor En Yun Hsu oversaw the construction of a 115-foot-long artificial wave machine in the Department of Civil Engineering. “We are merely scratching the surface of the ancient problem of how waves are formed and behave,” Hsu said.(24)

Mechanical Engineering student Victor Scheinman with a prototype hydraulic arm, 1969. The arm, now on display inside the Gates Computer Science Building, was one of two that were mounted to a table where researchers and students used it for research and teaching purposes for over 20 years, often focused on applications in the manufacturing industry. In 1974, a version of the Stanford Arm was able to assemble a Ford Model T water pump. | The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

Students demonstrating against the invasion of Laos by the South Vietnamese with U.S. air support, 1971. The students seized the Computation Center during 12 hours of confrontation and violence to protest the center’s use for war research. There were 12 arrests and no injuries. | Jose Mercado/Stanford News Service.

Students in the Design Engineering class, 1968 and 1969. In the late 1950s, Stanford Engineering’s Mechanical Engineering Design Division pioneered a new approach to engineering and design education, emphasizing hands-on, experiential learning through environments, including the Design Loft and Machine Shop (today, Product Realization Lab). Under the leadership of faculty John E. Arnold and Robert H. McKim, the Product Design program focused on teaching design as a creative practice, integrating engineering, arts, natural science, social science, and the humanities into a comprehensive design education to address real-world needs. The division aimed to prepare engineers who developed the ability to integrate technical and artistic skills with social and environmental understanding to create innovative solutions for complex challenges. This comprehensive design approach set the foundation for a broader emphasis on interdisciplinary design, which later influenced the emergence of design practices like Smart Product Design and Interaction Design and, eventually, the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (d.school). | Stanford News Service.

Tele-education

Bay Area engineers. The Honors Cooperative would eventually be folded into the Stanford Center for Professional Development (SCPD) in 1995 and, by the late 1990s, offer courses at three hundred companies.(25)

The control room for the Stanford Instructional Television Network (SITN), showing James Angell lecturing, 1969. This network allowed employees of member companies within a 50-mile range of Hoover Tower to take classes offered by the School of Engineering as part of the Honors Cooperative Program (HCP). When the HCP was founded in 1954, students had to come to campus to attend classes. With the founding of SITN in 1969, students could begin attending the program remotely. The network eventually became part of the Stanford Center for Professional Development. | Special Collections & University Archives.

Growing diversity

In 1968, Stanford student Barbara Liskov became the first woman at Stanford University to earn a PhD in computer science. Forty years later, Liskov would become the second woman ever to receive the A.M. Turing Award.(26) In 1969, Stanford’s chapter of the undergraduate engineering honor society, Tau Beta Pi, inducted its first female members.(27)

When Joseph Pettit stepped down as dean of the School of Engineering in 1972, William M. Kays, professor of mechanical engineering, served as his successor for the next dozen years. Under Kays, each of Stanford’s engineering departments consistently ranked in the top five in its field nationally, and the school increased its external research funding. Kays also led the diversification of the School of Engineering faculty and student body, recruiting women and underrepresented minorities.(28)

Barbara Liskov, the first woman to receive a PhD in computer science from Stanford University, 1968. She was also among the first women to receive a PhD from a computer science department in the United States. For her PhD, Liskov worked with John McCarthy, focusing on chess endgames. In 2008, she became the second woman to receive the A. M. Turing Award. | Kenneth C. Zirkel/Wikimedia Commons.

William M. Kays, May 1971. Kays began his career at Stanford as an undergraduate in engineering (’42), earned his MS (’47) and PhD (’51) in mechanical engineering, and went on to join the faculty in that department. By 1961, he was department chairman and in 1972 was appointed dean of the School of Engineering, in which role he served until 1984. Under Kays’s leadership, all of Stanford’s engineering departments ranked in the top five in their graduate fields nationally. The school increased its external funding of research and expanded the number of students, particularly women. The Center for Integrated Systems and the John A. Blume Earthquake Engineering Center were both established during his tenure. | Jose Mercado/Stanford News Service.

Clayton Bates, professor of materials science and engineering and of electrical engineering, 1974. In 1972, following a 10-year career in industry, Bates became the first Black faculty member to hold a tenure-track appointment in the School of Engineering. Along with a group of graduate students, Bates founded the Stanford Society of Black Scientists and Engineers, an affiliate chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers. He also acted as a mentor and supporter of Black students in the areas of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics and advocated for equity in STEM education. His expertise was in solid-state physics, and he was particularly interested in photoelectronic materials and devices. His work focused on the unraveling of processes involved in the interaction of photons and electrons with the very complex materials used in photoelectronic sensing devices. | Stanford News Service.

Clayton W. Bates Jr., an expert in solid-state physics and photoelectric devices, became the first Black faculty member in a tenure-track position in the School of Engineering in 1972. Pushing the frontiers of science was “what keeps us going. . . . Some people call research a rat race, but I don’t know of anything else in the world I would rather be doing,” Bates told Stanford News in 1983.(29)

In 1972, Stanford Engineering also began a concerted effort to recruit women into engineering.(30) Kays penned a booklet, “Women in Engineering: Consider the Possibility,” that was mailed to 12,000 high schools nationwide. In it, he noted, “As the father of four college-aged girls, I am well aware of the career ambitions of today’s women. . . . Now is the perfect time for women to break some new ground. Like it or not, you live in a highly technological society; technology is not going to go away, and you should be a part of it.”(31)

In 1973, just a year after Kays’s entreaty, the Department of Materials Science and Engineering awarded its first PhDs to women—Ayse Emel Geckinli and Diane Margel Robertson. A year later, Kays supported the creation of the Stanford Center for Research on Women, now known as the Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research.(32) He later encouraged the formation of the campus group Women in Science and Engineering (WISE).

A nobel prize

Kenneth Arrow, professor of operations research, at his press conference after winning the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences 1972. Arrow was on the faculty at Harvard University when he won the Nobel Prize for work he did while at Stanford for “pioneering contributions to general economic equilibrium theory and welfare theory.” Arrow returned to Stanford in 1979 and stayed until his retirement in 1991. | Chuck Painter/Stanford News Service.

In 1972, Kenneth Arrow, deemed one of the most influential economists of the twentieth century, was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics for work he did while at Stanford with collaborator Sir John Hicks on general equilibrium and welfare theories. That work is now fundamental in the evaluation of business risk and in government economic and welfare policies. Arrow had come to Stanford in 1949 and eventually became a professor of operations research. He played a defining role in the creation of the School of Engineering’s Department of Operations Research in 1967. Though he left Stanford in 1969 for Harvard University, where he was on faculty when he won the Nobel Prize, Arrow would return to Stanford in 1979, completing his distinguished career in 1991.(33)

New focus on the environment

The first Earth Day in 1970 spurred a period of profound growth in environmental awareness. Civil engineering faculty members James Leckie, Gilbert Masters, and Lily Young, with mechanical engineer Harry Whitehouse, developed an “immensely successful” course known as “Designs for Alternative Lifestyles” as part of the Stanford Workshops on Political and Social Issues. The team followed with a widely adopted textbook detailing environmentally beneficial projects that individuals could undertake at home. The Sierra Club published the book in 1975 as Other Homes and Garbage: Designs for Self-Sufficient Living.(34)

In 1974, the Environmental Engineering and Science program, part of the Department of Civil Engineering, partnered with the Santa Clara Valley Water District to explore how chemicals moved through highly treated Palo Alto domestic wastewater and into an aquifer adjacent to San Francisco Bay. Water Factory 21 became the first treatment plant to use reverse osmosis to remove harmful organic chemicals from treated wastewater.(35)

“We expect that more and more graduates will enter the environmental field. Society is fully aware of needs in relation to ecology, and more engineers will be needed in planning and building sewage treatment and power plants, transportation, and with other expertise related to the environment,” wrote Assistant Dean Alfred Kirkland in 1972.(36)

Rising demand

Dean Pettit had boldly predicted a substantial shortage of engineers by decade’s end. As the demand for engineers grew throughout this transformative decade, enrollment in the School of Engineering increased dramatically, feeding a need for 42,000 new engineers a year nationwide.(37) The school’s growth mirrored the nation’s increasing reliance on engineers to address complex global challenges. As its fifth decade closed, the School of Engineering had firmly established itself as a leader in shaping the future of technology and innovation. And it was poised to continue setting the pace for engineering education and research, extending influence far beyond the classroom and laboratory.

Engineering Corner, 1974. The new shield design for the School of Engineering, introduced in 1967, was added to the building in the early 1970s, before the school moved into its new home in the Terman Engineering Center in 1977. The mascle (diamond with the center removed) framework is orange, engineering’s academic color, on a blue background, denoting Stanford Engineering’s commitment to graduate education. The triple redwood fronds, found on all Stanford University heraldry, symbolize, first, “the organization, transmission, and generation of knowledge which takes place in the School and on which the scholarly growth of engineering depends,” and, second, “the tripartite character of Stanford’s School of Engineering—students, faculty, and alumni.” | Special Collections & University Archives.

Explore more stories

The Terman era

Decade 3

100 Years of Stanford Engineering

A Century of Innovation

Share your Stanford Engineering memories

Be a part of the celebration

As we celebrate the school’s Centennial anniversary, we invite you to mark this milestone by sharing one of your favorite memories of Stanford Engineering. We’d love to hear from you and will be re-sharing selected memories in a variety of ways both publicly and privately throughout the year. Please note: not all submissions will be shared publicly.