The Terman Era

1945 – 1954

Left to right: David Packard, William Hewlett, and Dean of Engineering Fred Terman attend the dedication of the Hewlett-Packard wing in Stanford’s Electronics Research Laboratory, 1952. | Stanford News Service.

Stanford is not only doing more and higher quality research in engineering than would otherwise be possible, it is also training more graduate students, and is training them better than ever before."

— Frederick Terman, 1948

1945 – 1954

Samuel Morris recommended Frederick Terman to be his successor as dean of the School of Engineering. Terman, on leave from Stanford at the time, had been serving since 1942 in a wartime appointment as head of the top-secret Radio Research Laboratory at Harvard University. Yet throughout the war, Terman was anticipating a period after the war he believed would be defined by unprecedented technological advancement led by engineers.(1)

Despite Terman’s absence, in December 1944 Stanford President Donald Tresidder named Terman the third dean of the Stanford School of Engineering, with a strong endorsement from the engineering faculty. “Dr. Terman’s scholarly contributions in the field of electrical engineering and his administration of one of America’s largest war research projects place him among the outstanding engineers in the country,” Tresidder said, announcing Terman’s appointment.(2)

Once he was back in Palo Alto, Terman’s first order of business was to prepare the university for the expected influx of students attending American universities on the GI Bill. Those students would need housing, new classrooms and labs, and new faculty to lead the way. Terman laid out a “Plan for 20 Years of Greatness” that would see “Stanford’s engineering and physical sciences departments developing in size and quality of research, especially in fields pursued during the war.”(3) In President Tresidder’s annual report, Terman wrote in August 1946: “The year that has just been concluded has been one of change and readjustment in that it has marked the transition from war to post-war conditions. Those faculty members who had been on war service returned during the year, and by the end of the Summer quarter the pre-war faculty had been restored.”(4)

The school quickly rebounded from record-low wartime enrollments. Between the fall and spring quarters of 1945–1946, the “civilian engineering” program tripled in size. The expansion was so great that Terman broadened summer quarter offerings to meet the demand. The influx of students was felt across Stanford: in winter 1946, university enrollment was 7,000, with housing for only 4,000; a year later, enrollment was 8,203.

The year that has just been concluded has been one of change and readjustment in that it has marked the transition from war to post-war conditions. Those faculty members who had been on war service returned during the year, and by the end of the Summer quarter the pre-war faculty had been restored."

— Fred Terman

The school quickly rebounded from record-low wartime enrollments. Between the fall and spring quarters of 1945–1946, the “civilian engineering” program tripled in size.(5) The expansion was so great that Terman broadened summer quarter offerings to meet the demand. The influx of students was felt across Stanford: in winter 1946, university enrollment was 7,000, with housing for only 4,000; a year later, enrollment was 8,203.

On the administrative front, in 1946 the Department of Mining was at last merged with the Department of Geology and moved from the School of Engineering into the School of Earth Sciences as the Department of Mineral Sciences. Terman also transitioned the standard engineering degree from a bachelor of arts (BA) to a bachelor of science (BS) to reflect the growing technical demands of the curriculum.

Harnessing Federal Funding

Before and even during the war, the School of Engineering’s share of federal research dollars had been limited, and the School of Engineering budget for the 1946–1947 school year had reached its lowest level since 1926.(6) Terman refused to accept the status quo and in the postwar period looked for opportunities to expand funding. Reporting on federal contracts from the Navy’s Office of Research and Inventions of the Navy (later the Office of Naval Research), Army Air Force, Signal Corps, and the National Bureau of Standards, he wrote to President Tresidder in 1946 that “A substantial proportion of the Dean’s time has been devoted to the establishment of a research program having long range values, sponsored by government agencies....[A]nd the program is still expanding.”(7)

Research dollars flowed westward from Washington. Within months of returning to campus, Terman had secured government-funded projects totaling $380,000 per year, including $210,000 for electrical engineering, $81,000 for mechanical engineering, $59,000 for physics, and $30,000 for chemistry.(8) By 1948, government-sponsored research in civil, electrical, and mechanical engineering neared a half million dollars(9)—roughly $6.5 million in inflation-adjusted dollars today.(10)

Notable among the many new initiatives at Stanford was the 1945 establishment of the Microwave Laboratory, which Terman had orchestrated even while stationed across the country. Centering the Microwave Lab in the School of Physical Science but sharing close ties to the School of Engineering was typical of the School of Engineering’s emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration. Director William Hansen, a physicist, had selected Edward Ginzton, an engineer, as his second in charge and appointed him associate professor of “applied physics”—a neologism highlighting the “interdisciplinary contours of physics and electrical engineering at Stanford.”(11) In 1947, Hansen and Ginzton used klystrons to create the first linear electron accelerator.(12)

Professor Edward Ginzton, left, and Dr. Henry Kaplan, a Stanford Medicine radiologist, in front of klystron gauges, circa 1953. Kaplan and Ginzton coinvented North America’s first medical linear accelerator, a 6-million-volt machine constructed at the Stanford Medical Center, then in San Francisco. The Stanford device was first used in 1955, soon after a similar device debuted in England. | Stanford News Service.

Edward L. Ginzton with the Mark III linear accelerator, 1951. Ginzton earned his doctorate in electrical engineering at Stanford and was later appointed as a professor of electrical engineering and applied physics. He led a Stanford team that designed the world’s most powerful particle accelerator. | Stanford News Service.

Mark III linear accelerator, 1952. This was one of many similarly named accelerators and detectors created and used at the Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory (HEPL) and at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC). | Stanford News Service.

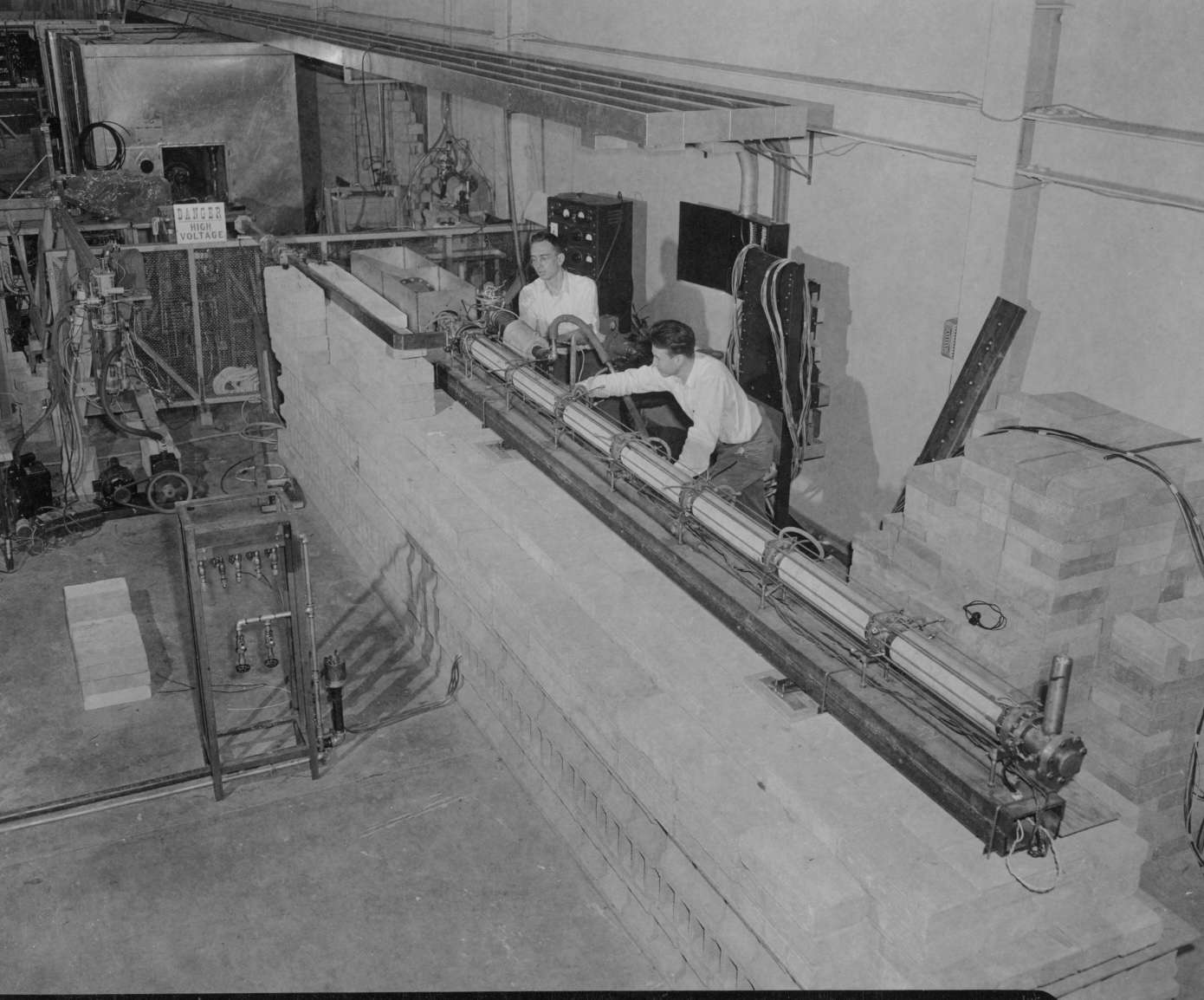

First section of the Mark III linear accelerator, 1949. The accelerators were all built on campus at the Hansen Experimental Physics Lab (HEPL) and were precursors to the 2-mile accelerator later built at SLAC, the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. | Stanford News Service.

William W. Hansen with the 3-foot Mark I electron linear accelerator prototype, 1947. It was built, as all the Mark accelerators were, in the basement of the physics department in the Hansen Experimental Physics Lab (HEPL). | Stanford News Service.

Felix Bloch, right, and William Hansen demonstrating a working model of equipment used in their research, 1947. Bloch, a Stanford professor of physics, invented a new technique of qualitative analysis by nuclear reaction; William Hansen was director of the Stanford Microwave Laboratory. | Stanford News Service.

Electrical engineering faculty Oswald Garrison Villard, Jr. (MEng ’43, PhD ’49), right, and Allen M. Peterson (BS ’48, MS ’49, PhD ’52) with equipment used to record meteors in the ionosphere, August 1950. Their pioneering work on reflecting radar signals off the ionosphere led to Villard’s 1959 debut of “over-the-horizon” radar, which transcended line-of-sight limitations and laid the foundation for advanced long-range surveillance and missile detection systems. | Special Collections & University Archives.

The Microwave Lab would exceed even Terman’s high expectations, eventually producing fundamental research in nuclear physics, high-powered microwave tubes, microwave and transistor engineering, and plasma and laser physics. In the following decade, it would be developed into the Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC), which would later grow into “a huge federal research facility.”(13)

Strategy for growth

Terman imagined nothing less than a “great new era of industrialization” for the American West, a transformation led by the West’s own intellectuals—preferably trained at Stanford. “[I]ndustrial activity that depends upon imported brains and second-hand ideas cannot hope to be more than a vassal that pays tribute to its overlords, and is permanently condemned to an inferior competitive position,” Terman wrote.(14) Western universities, he believed, “can train the type of men required to exercise leadership in an expanding industry. They can be a source of ideas, and of inspiration that stimulates people to new accomplishments.(15)

Aerial view showing the Stanford Industrial Park area before major development, ca. 1953. | Hatfield Aerial Surveys / Special Collections & University Archives.

[Western universities] can serve as catalysts that speed the reaction by which the discoveries of pure science are turned to practical uses that advance industrial technology and create new industries.”

— Fred Terman

Robust funding made new achievements possible. “Stanford is not only doing more and higher quality research in engineering than would otherwise be possible, but it is also training more graduate students, and is training them better than ever before,” Terman wrote in 1948.(16) The university’s status, Terman said, demanded “an understanding of what it is that being at the top represents. The most important measure of success is in terms of student output, which must be large in number and outstanding in quality.”(17)

Terman set about a new strategy of carefully selecting fields of study for which he would deliberately—and aggressively—select and recruit faculty, an approach he called “steeples of excellence.”(18) He chose fields of highest priority to Stanford’s western region—such as oil, geology, heat transfer, and chemical engineering—and also fields with the most rapid growth—such as radio, electronics, and mechanical structures. For faculty, he wanted not the greatest numbers, but the greatest achievers, whom he found in recruits like Stephen Timoshenko, whose work defined an entire era in mechanical and civil engineering. Terman also fought for higher salaries for faculty, whose pay trailed both that offered by other leading universities and, especially, that offered by industry, where a highly trained engineer could make several times the pay of a university professor—a challenge that persists today.

Terman also fought for promotions for various non-faculty lecturers and “teaching specialists.” One such advancement went to Irmgard Flügge-Lotz, who had become a lecturer in 1949 and finally, in 1960, became the first female professor at the School of Engineering. The author of four dozen or more academic papers and two books, Flügge-Lotz was respected for her work in aerodynamics and automatic control theory. She was particularly known for the Lotz Method for predicting aerodynamic lift on airplane wings, which was adopted as standard in the field.

Stephen P. Timoshenko teaching a class, 1948. A renowned expert, teacher, and writer widely regarded as the “father” of applied mechanics in the United States, he was born in the Russian Empire in 1878. Timoshenko taught at Stanford from 1936 to 1963 and was instrumental in the formation of the Division of Engineering Mechanics in 1949. | Special Collections & University Archives.

As the 1950s opened, the Korean conflict accelerated the rise in government-sponsored radio and electronics research at Stanford.(19) Terman had been planning for an Electronics Research Laboratory (ERL), which opened in 1951, to coordinate research operations in electrical engineering.(20) The Office of Naval Research said in 1950 that it saw Stanford as “about first in usefulness,” among engineering partners, promising to invest a million dollars in “fast-paced electronics research” at the school.(21)

The ERL was soon pulling in so much research funding, $700,000 per year, that an expansion was approved in November 1951, just months after the laboratory opened; the Applied Electronics Laboratory (AEL) was added in 1958.(22) True to Terman’s no-nonsense style, the ERL and AEL buildings were practical concrete-and-wood structures designed not for comfort or aesthetics but for serious science. They would serve Stanford engineering students for another forty years.(23)

Images left and right. Housed in utilitarian buildings, the Electronics Research Laboratory (ERL) opened in 1951 and provided space for coordinating research operations in electrical engineering. The ERL was soon drawing $700,000 per year in research funding, resulting in expansion plans for an Applied Electronics Laboratory (AEL), approved just months later. | Stanford University Planning Office.

Unleashing the Power of Computation

In 1953, Stanford established its first Computation Center, where a single high-speed IBM Card-Programmed Calculator churned through mountains of computations. The center was in such high demand that use of the Computation Center was reserved for faculty and graduate research only. Stanford’s first true computer, an IBM 650, would not arrive until 1956.(24) The Computer Science Department was originally in the Department of Mathematics in the School of Humanities and Sciences, where it remained until 1985, when it was moved to the School of Engineering.

John G. Herriot, professor of mathematics, when he became the first director of the newly founded Computation Center in 1953. In spring 1955, he taught the first programming course, “Theory and Operation of Computing Machines,” to twenty-five students using an IBM Card-Programmed Calculator, Model II. Computer Science was in the Department of Mathematics until 1985, when it was moved to the School of Engineering. | Stanford News Service.

The Honors Cooperative Program

In addition to seeking federal funding, Terman was a proponent of close associations between academia and industry to advance research while providing employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for graduates. In 1954, he inaugurated the Honors Cooperative Program, which welcomed working electrical engineers who wanted to earn a master’s degree part-time while they were still employed. Under the program, four companies—Sylvania Corporation, Hewlett-Packard, Stanford Research Institute, and General Electric—signed five-year agreements through which they selected qualified employees to enroll. At six credits per quarter, a candidate could earn a master’s degree in two calendar years, a service for which the companies gladly paid double Stanford’s standard tuition.(32) Over the years, the Honors Cooperative Program has provided thousands of engineers with career-changing graduate degrees, with a marked effect on the “innovation ethos” that has set Silicon Valley apart. The Honors Cooperative Program remains a key feature of the Stanford Engineering Center for Global and Online Education and, seven decades later, continues to play an important role in Silicon Valley.(33)

Irmgard Flügge-Lotz

Irmgard Flügge-Lotz. | Stanford News Service.

“A Life Which Would Never Be Boring”

As a child in Germany, Irmgard Flügge-Lotz lived near the home of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin. She later recalled that witnessing his tests of huge airships was a thrill that stayed with her and fueled her desire to understand the science of flight.(25)

Early in her career, Flügge-Lotz became known for the Lotz Method, her process for calculating the spanwise lift distribution of airplane wings, which became an international industry standard.(26)

In 1948, she and her husband, Wilhelm Flügge, accepted offers from Stanford Engineering. Flügge-Lotz left her position as chief of a research group in theoretical aerodynamics at the French National Office for Aeronautical Research (ONERA) to bring her expertise in automatic control theory to Stanford, where she served as a lecturer. In September 1960, she became the first female professor in the School of Engineering, appointed in both aeronautical engineering and engineering mechanics.

Flügge-Lotz was recognized for her enthusiasm and expertise in fluid mechanics—particularly in boundary-layer theory and numerical models. She taught courses on boundary-layer theory; introduced a novel, year-long sequence of courses in mathematical hydro and aerodynamics; developed new courses in the theory of automatic controls; advised doctoral students for dissertations in aerodynamic theory; and established the weekly Fluid Mechanics Seminar, which continues at Stanford today.(27)

A supportive advisor, Flügge-Lotz would publish reports on automatic control devices with her students. Because these devices were often electrical, the studies often led to increased contact and collaboration with faculty and students from the Department of Electrical Engineering.(28)

Reflecting on her life, Flügge-Lotz said, “I wanted a life which would never be boring. That meant a life in which always new things would occur.”(29) She felt most satisfied when she had “an interesting problem that has resisted being solved, and then solving it.”(30)

Her contributions have spanned a lifetime during which she demonstrated, in a field dominated by men, the value and quality of a woman’s intuitive approach in searching for and discovering solutions to complex engineering problems."

Leaders at the University of Maryland

Flügge-Lotz made numerous mathematical contributions to the fields of aerodynamics and automatic control theory. She published more than fifty technical papers, authored two books, and paved the way for more women in engineering in the years to come. In the citation of her 1973 honorary doctorate, leaders at the University of Maryland wrote, “Her contributions have spanned a lifetime during which she demonstrated, in a field dominated by men, the value and quality of a woman’s intuitive approach in searching for and discovering solutions to complex engineering problems.”(31)

—Hanna Ahn

Assistant University Archivist for

Special Collections & University Archives

First Steps to Semiconductors

After the demonstration of the world’s first transistor in 1947, Terman sought during the early 1950s to make Stanford a leader in solid-state electronics and in the study of semiconductors. His handwritten notes from 1948 show his emerging interest in the promising field. With characteristic understatement he wrote, “The transistor is a great new force that will revolutionize many aspects of electronics in the next five to ten years.”(34)Achievements in the decade to come would prove him correct.

Unimagined horizons lay ahead for engineering, for the school, and for Terman himself. As the school’s third decade came to a close, the Fred Terman era was etched into history.

Explore more decades

A period of transformation

Decade 4

Share your Stanford Engineering memories

Be a part of the celebration

As we celebrate the school’s Centennial anniversary, we invite you to mark this milestone by sharing one of your favorite memories of Stanford Engineering. We’d love to hear from you and will be re-sharing selected memories in a variety of ways both publicly and privately throughout the year. Please note: not all submissions will be shared publicly.